Implementing neural turing machines in pytorch

A feed-forward neural network doesn’t have memory. It receives an input and gives back an output, but it has no way to remember anything by itself. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have some kind of memory and show dynamic behaviour. Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM) - a special type of RNN - are better at remembering long-term dependencies and are the benchmark to beat when it comes to sequences.

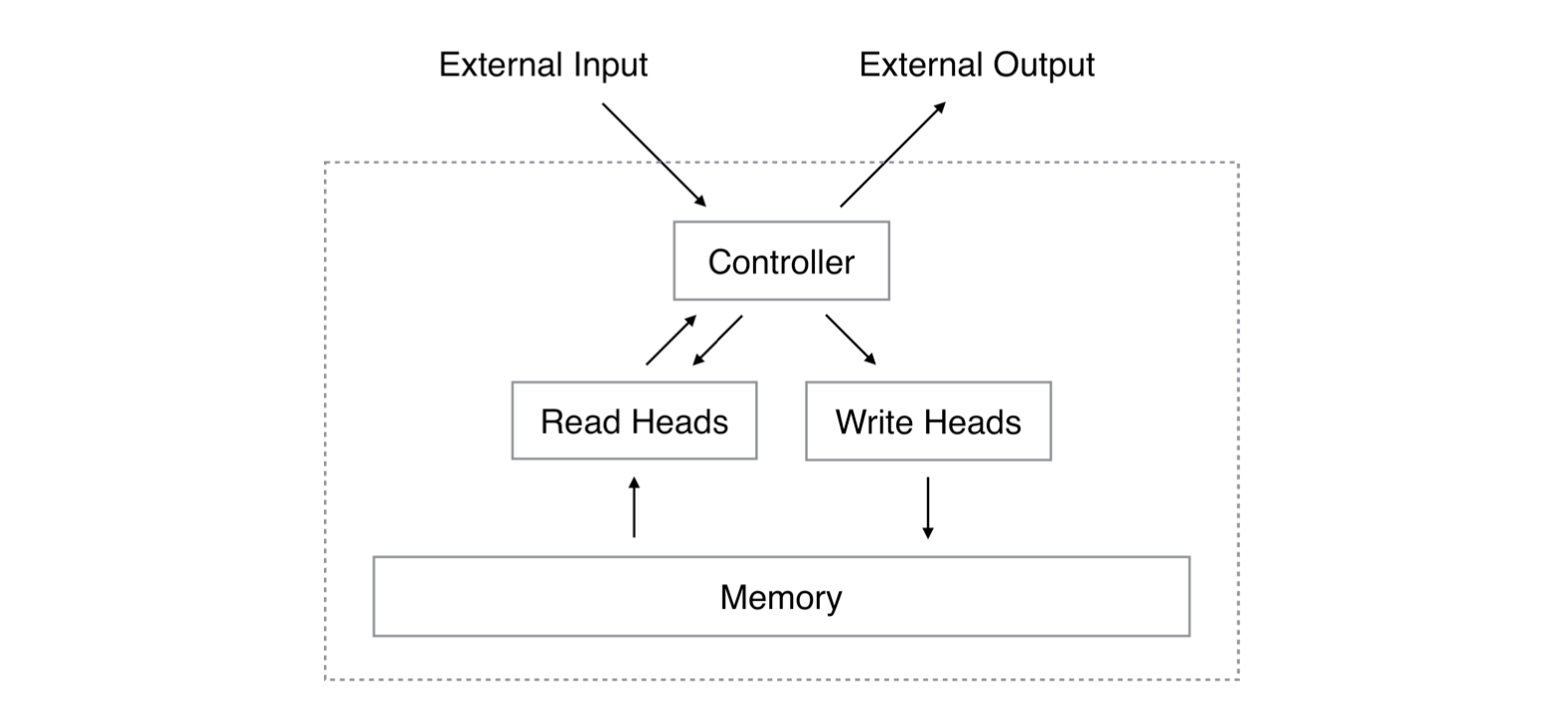

A Neural Turing Machine (NTM) is a different type of neural network, introduced in Graves et al (2014). Like a LSTM it can process sequences of data. Unlike LSTMs, it has two components: a neural network controller and a memory bank. The controller is free to read and write to its memory. All read and write operations are differentiable, which makes it an end-to-end trainable model. It learns what to store and what to fetch from its memory table.

Why is this cool? Because it has access to a memory bank, a NTM needs fewer parameters than a LSTM and can more easily learn some algorithmic tasks. It trains faster and better.

I’ve wanted to implement NTMs for a while. I find the concept of a neural network with memory fascinating and hope we see more applications in the future.

I’m happy to release a NTM pytorch implementation I’ve been working on: https://github.com/clemkoa/ntm.

The analogy with Turing machines is made because of the access to memory. Even though the network outputs that define read/write operations are called “heads”, they are just regular neural layers.

I made my own implementation for two reasons:

- reproducibility: the results in the paper are quite interesting, and I wanted to see if I could reproduce them myself

- understanding: I wanted to have a proper understanding of the architecture. Implementing this paper is also a good exercise for machine learning engineers. The paper defines all the steps and transformations to achieve the results, it’s then up to you to make it work in practice.

This post will go over the results I got from my implementation, as well as a few things I learnt in the process.

Why pytorch?

Pytorch is my go-to framework for any deep learning project. It allows me to write light and readable code. The syntax and APIs are amazing, and it’s pretty fast. The only thing I have against it is the documentation, but hopefully it improves in the not so distant future.

Results

I was able to reproduce the authors’ results on a set of tasks using the same experimental parameters they described.

1. Copy

The copy task tests whether NTM can store and recall a long sequence of arbitrary information. The network is presented with an input sequence of random binary vectors followed by a delimiter flag. The target sequence is a copy of the input sequence. To ensure that there isn’t any assistance, no inputs are presented to the model while it receives the targets.

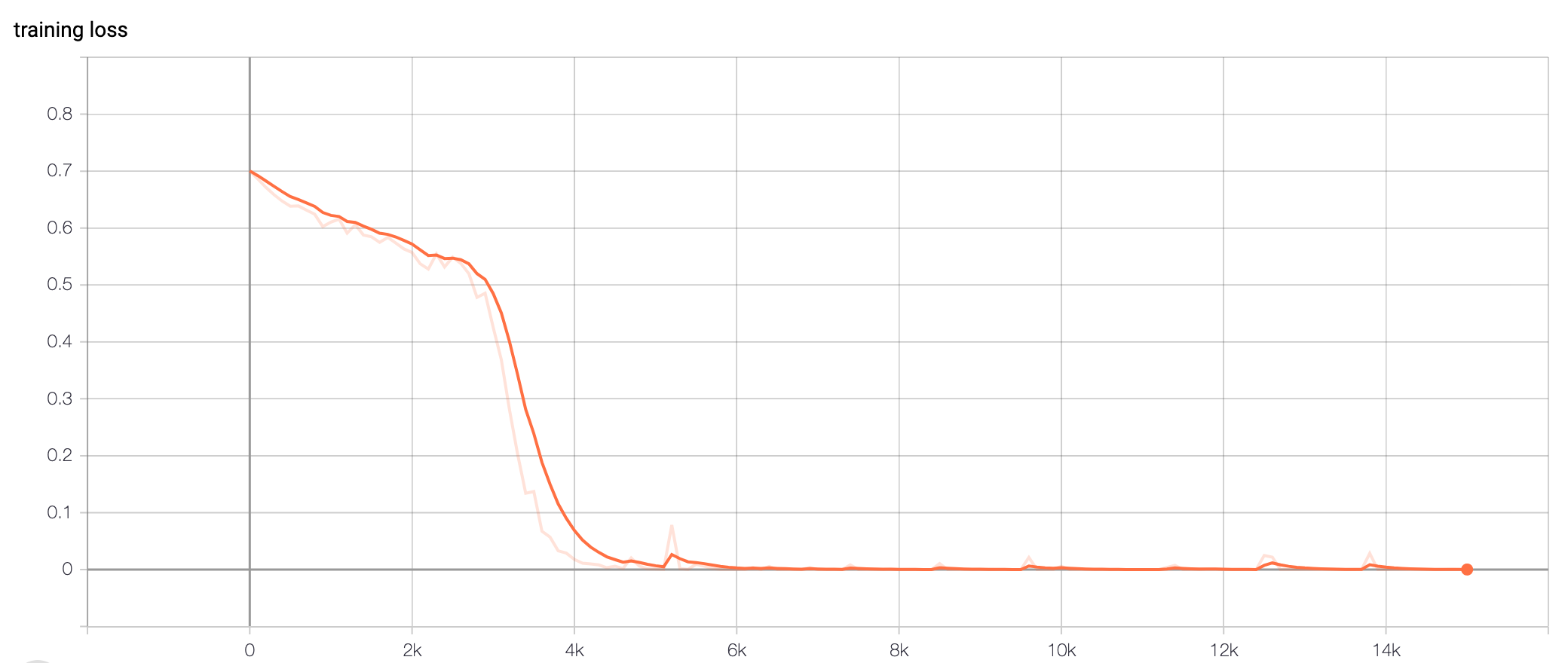

On this task, the model trains very well on sequences between 1 and 20 in length. A LSTM controller gives the best results and seems to always converge perfectly within 50k sequences.

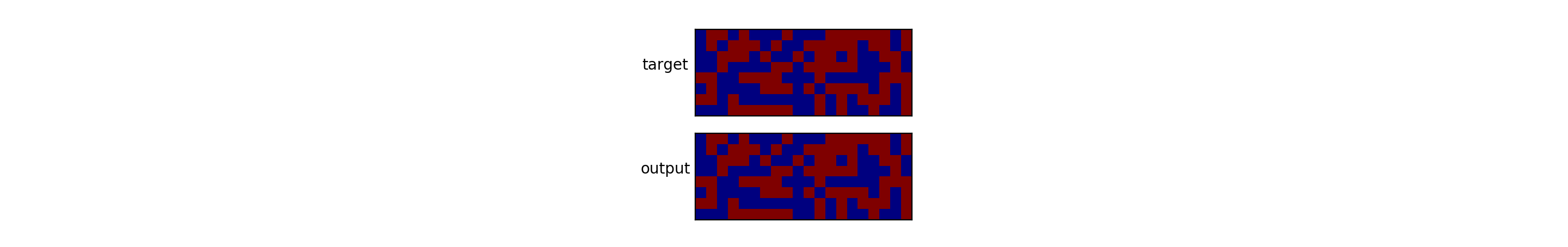

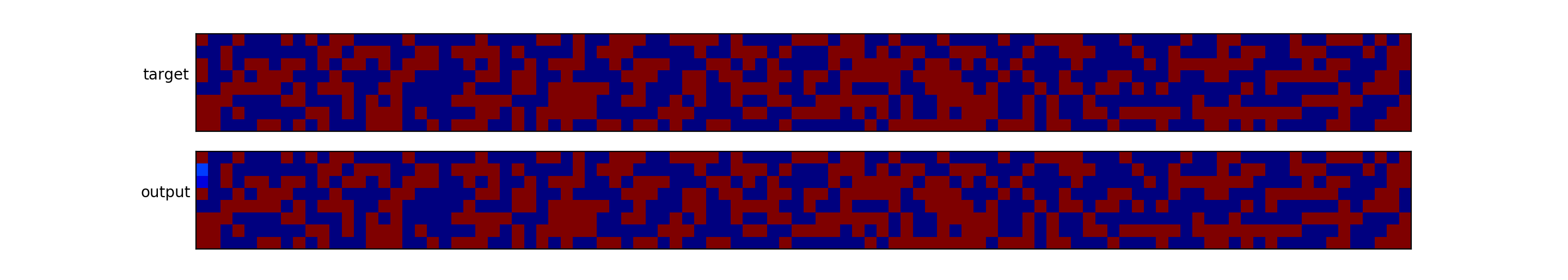

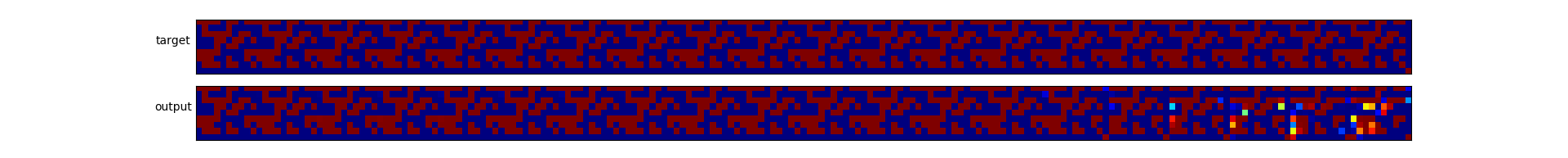

Here is the net output compared to the target for a sequence of 20. As you can see, it’s perfect. 😎

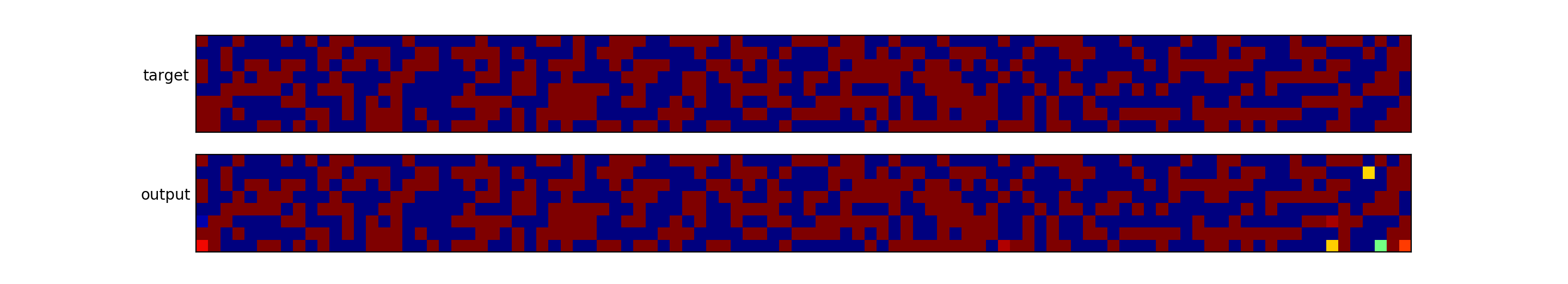

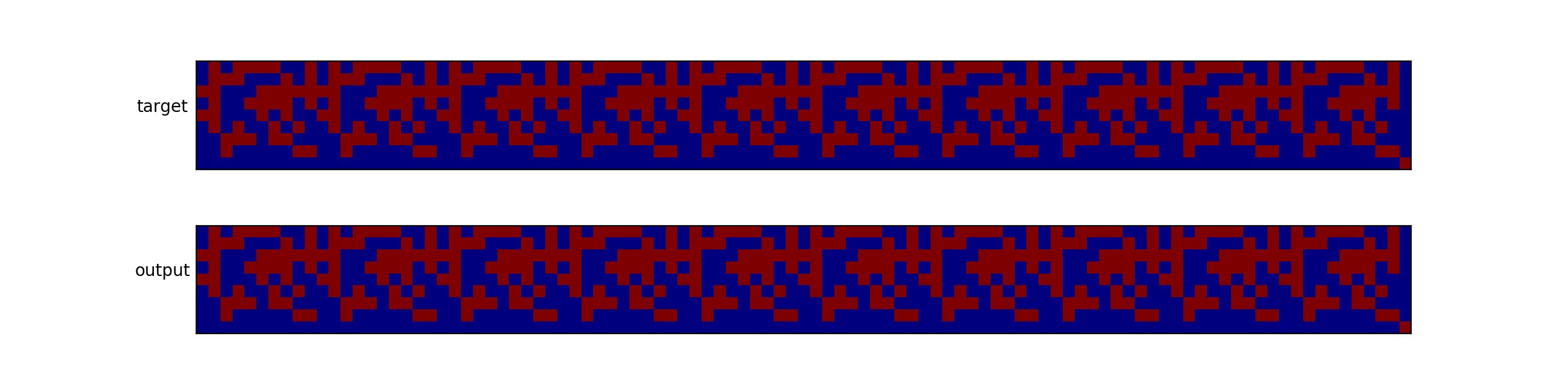

Here is the net output compared to the target for a sequence of 100. Note that the network was only trained with sequences of 20 or less.

Here is the same sequence for a model trained on a different random seed: 20k iterations, batch size of 4 and seed of 1. Only the first vector has a slight issue.

It is surprising how well the model can generalise the task at hand, at a relatively low cost. There are only 67,000 parameters and the model reaches a loss of 0 very fast.

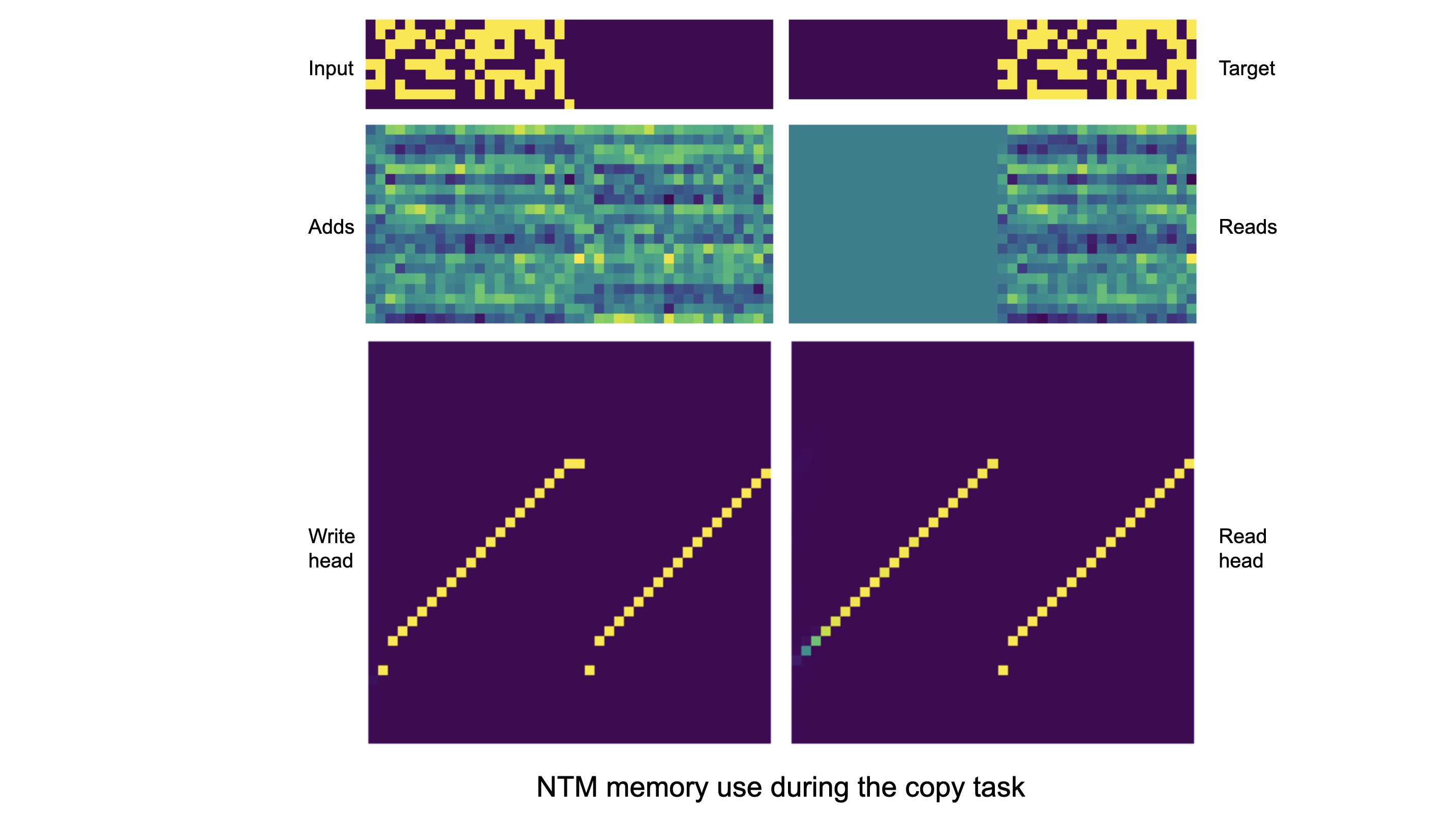

The following image shows the memory use during the copy task.

Top row are input and target. You can then see the writing vector (middle left) as well as the read vector (middle right). On the bottom row is the weight vector from write and read heads. Only a subset of memory locations are shown.

Note the sharp focus of the weightings: purple is 0, yellow is 1. The fact that the focus moves at every steps shows the network’s use of shifts for location-based addressing. We also note that the read vector is constant before the delimiter vector. The network knows not to read before it’s asked to give back the sequence.

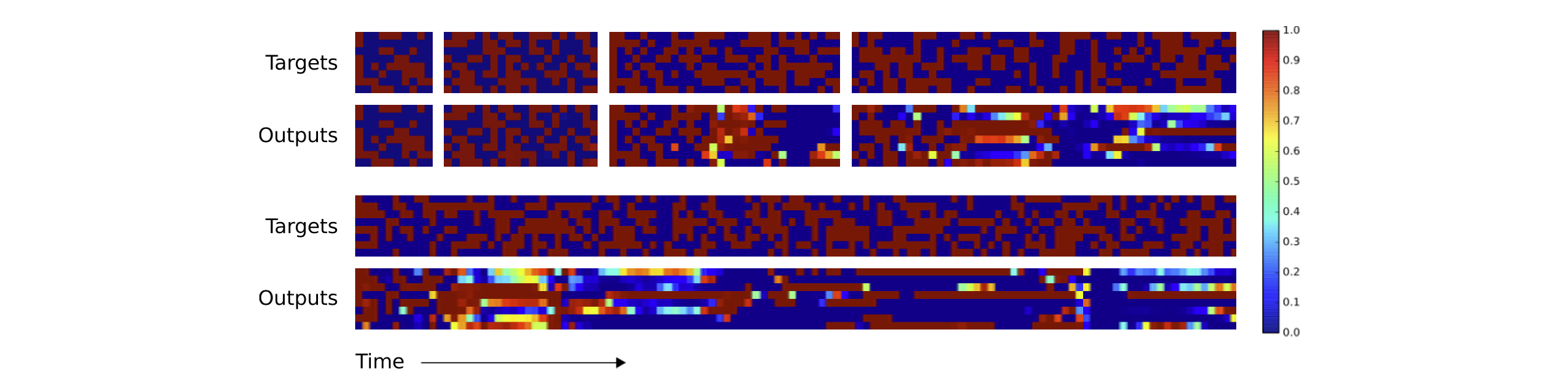

So how does the NTM compare with LSTM on this task? The authors were not able to reach a good output with a LSTM-only model, even when it had ~20 times the amount of parameters of the NTM (67k vs 1.35M parameters). We see on the image below that the number of correct vectors decreases with the length of the sequence.

This proves that NTMs are better suited than LSTMs for the copy task. They require less parameters and are able to generalise better.

2. Copy repeat

The copy repeat task is all about imitating a for-loop. As stated in the paper, “the repeat copy task extends copy by requiring the network to output the copied sequence a specified number of times and then emit an end-of-sequence marker.” The network receives a sequence of random 8-bit vectors, followed by a scalar value representing the number of copies required. No inputs are presented to the model while it receives the targets, to ensure that no assistance is given.

It is important to note that emitting an end-of-sequence vector is part of that task. Otherwise the model will only remember the sequence and repeat it indefinitely, without caring about the amount of repetition asked. To emit the end marker at the correct time the network must be both able to interpret the extra input and keep count of the number of copies it has performed so far.

The model is trained on sequences of 1 to 10 8-bit random vectors, with a repeat between 1 and 10. Here is the model output for a sequence of 10 and a repeat of 10.

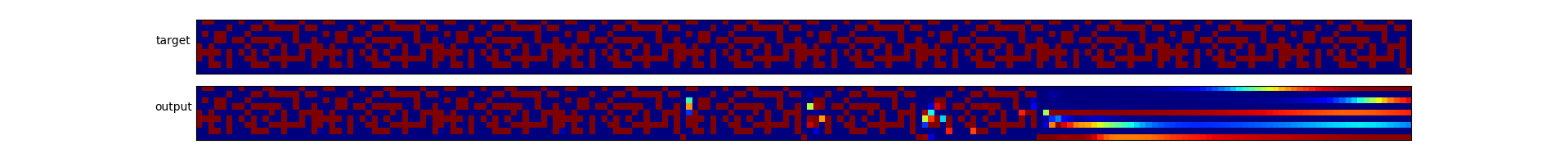

Here it is for a sequence of 10 and a repeat of 20. Note that the network was trained with a repeat of 10 max.

Here it is for a sequence of 20 and a repeat of 10. Note that the network was trained on sequences of 10 or less. Maybe it needs a bit more training 😬.

Training on the repeat copy task takes substantially longer than the copy task. It usually takes at least 100k iterations to start seeing good results.

Insights

1. Initialisation matters

Initialisation is a well-known matter when it comes to model training. If you’re unfamiliar with that problem, you can experience some of it here: https://www.deeplearning.ai/ai-notes/initialization/.

As explained in Collier et al. (2018), the initialisation of memory, read heads and write heads is a prime factor of convergence. Some NTM implementations on github initialise the memory read to a random vector, which seems counter-intuitive. It will make the network’s task harder by having to learn that random initialisation. Instead I initialise the memory read to a constant vector of small value (\(10^{-6}\)).

Initialising the state of read heads and write heads at the start of each sequence is another important step. It’s actually best to make it a learnt parameter of the model. This way the model will learn to optimise the head weights at the beginning of each sequence.

Without this initialisation scheme, I noticed that the network did not always converge depending on the random seed.

2. The intelligence is in the addressing mechanisms

I found each step of the addressing mechanisms to be necessary for the model to fit.

A step that took me a long time was the shifting process. Here is the equation described in the paper, expressed as a circular convolution:

\[w_t(i) = \sum_{j=0}^{N-1} w_t^g(j)s_t(i-j)\]As soon as I saw that I went to look for a circular convolution implementation in pytorch. My mistake was not reading the paper properly and thinking that \(s_t\) was the same shape as \(w_t^g\). So when I didn’t find anything that suited me, I implemented my own version of the circular convolution. And it worked, the model converged on the copy task!

Comparing my code to other public repos and reading back the original article, I found out that \(s_t\) was actually a vector of length 3. Each element is the degree of shifting by -1, 0 and 1. It turns out that the circular convolution described here is valid. I went with this implementation because it allows \(s_t\) to have a physical sense as well as fewer parameters.

In general, almost every sentence of section 3. of the original article is necessary to fully understand the architecture. It is definitely worth spending a few hours reading and re-reading that section before starting any implementation.

3. Adam is safe but RMSProp is better here

When implementing neural nets, I try to follow some principles/recipe to keep complexity at a reasonable level. Among them was using Adam as the optimiser, especially for RNNs. Andrej Karpathy said here that Adam is safe in the early stages of setting baselines.

While that’s true, Adam was sometimes really slow to make the model converge perfectly. The authors of the original article recommended RMSProp, so I used it and noticed it helped the model converge faster.

4. The controller needs the previous memory read as input

It’s a small detail that you can see from the architecture schema in the article: the read head output links to the controller. From my experience, feeding the controller both the input and the previous read helps learning better. It seems counter-intuitive at first, especially because the network is supposed to rely only on its memory bank.

What’s next?

For you

I’ve uploaded some trained models here. You’re welcome to try them by yourself with the library: https://github.com/clemkoa/ntm.

For me

Next is trying to implement more tasks described in the original article. Mainly associative recall and sorting. From what I’ve managed to do, it seems like my architecture is good enough and it’s just a matter of training the model on new tasks. I’d also like to spend some effort on the feed-forward controller, as it didn’t give viable results on the two tasks presented above.

References

- Graves, Alex, Greg Wayne, and Ivo Danihelka. “Neural turing machines.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.5401 (2014).

- https://github.com/loudinthecloud/pytorch-ntm/

- Collier, Mark, and Joeran Beel. “Implementing neural turing machines.” International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks. Springer, Cham, 2018.